June 2007

GQ Magazine

HAIL MARY, USA

In the middle of swampy southern Florida, Domino’s Pizza millionaire Tom Monaghan is building a town where the streets are named after saints, almost all the residents will be Catholic, and, if he has his way, no contraception or pornography will ever be sold. As Ave Maria begins to welcome its first residents, James O’Brien ventures to a place that would make the Vatican (Vatican I, that is) proud.

Photographs by Ofer Wolberger

The street grid of Ave Maria, Florida, is skewed precisely 2.49 degrees north of east so that the new city’s eastern avenues will catch the sunrise each March 25, the day on which Catholics traditionally mark the Feast of the Annunciation. The Annunciation is the day an angel appeared to Mary, unmarried virgin betrothed to carpenter Joseph, and announced to her that she was full of grace, that the Lord was with her, that she was blessed among women, and that the fruit of her womb, Jesus, was also blessed. From the words of the angel’s announcement comes the prayer close to the heart of any Catholic or any quarterback desperately scrambling as time runs out: the Hail Mary, or in Latin, Ave Maria.

You might think a town named for the Virgin, a town cofounded and funded largely by devout Catholic multimillionaire Tom Monaghan—and tied spiritually, geographically, and economically to the newly constructed campus of a Catholic university that he also founded—would choose to orient itself to mark the sunrise on Christmas Day. But you would be missing the ideological point. Life begins at conception, divine or otherwise; at that moment of divine impregnation 2,000 years ago, humanity’s hope for salvation through Jesus Christ began. These days, according to Monaghan, much of humanity, including many Catholics, has abandoned hope in favor of the ephemeral, possibly even satanic, comfort of secularism, represented most powerfully by the legal freedom of women to have abortions.

“That’s the battleground the opposition to the church has chosen,” he tells me. And so it is that opposition to abortion and, to a certain extent, to gay rights have become the pistons that fire many of Monaghan’s endeavors to save the church and the world.

I first meet Monaghan—who built Domino’s Pizza from one rinky-dink parlor in Ypsilanti, Michigan, into a billion-dollar business and who once owned the Detroit Tigers—in Naples, Florida, in his once in a pink stucco house on the temporary campus of Ave Maria University. (Monaghan founded what became AMU in 1998 in Ypsilanti in response to a belief that more established Catholic universities were losing their Catholic identity and piety.) This summer, AMU will move its operation from here to its new, permanent campus on the western edge of Ave Maria town. This month, the town of Ave Maria will begin welcoming its first residents, including Monaghan himself.

Monaghan is slight and dapper, in a blue business suit. At 70, he has an outstanding head of Bob’s Big Boy brown and gray hair, big glasses, and poor hearing. He speaks in a halting midwestern drawl that I suspect has fooled a few people along the way into thinking he is simple, which he is not.

In 1943, Monaghan’s widowed mother turned 6-year-old Tom and his younger brother over to a Catholic orphanage in Jackson, Michigan, where he lived until he was 12. Over the years, Monaghan has described life at the orphanage as downright Dickensian, and yet today he talks with reverence and gratitude about the good things he took away from St. Joseph’s. One was his religion.

“If I didn’t have my faith” he tells me, “I’d make Hugh Hefner look like a piker.”

Somehow the other lasting love he carried out of the orphanage was for architecture, particularly the work of Frank Lloyd Wright. Indeed, as a child, he expected to be either a priest or an architect, or possibly that rare hybrid, a priest-architect. But he never finished college. The pizza joint he bought to help pay for school after a stint in the Marines was just too taxing. And then too busy, and then too lucrative.

Even as he acquired towering wealth and all the nouveauriche accoutrements of a titan, Monaghan says he began to see the success of Domino’s in terms of how he could use it to help the church. And in 1991, Monaghan made a dramatic about face after reading the chapter on pride in C. S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity. Lewis called pride the “essential vice, the utmost evil.” By pride, Lewis meant competitiveness, the need to possess more than the next guy. His words seem to have sent a dagger into the ultra-acquisitive heart of Monaghan and, at least in part, inspired him to convert from the most conspicuous of consumers to a poverty-seeking millionaire.

He sold off the Sikorsky S-76 helicopter, the schooner christened Domino Effect, the Lake Huron island resort, and 244 cars, including an $8 million Bugatti Royale and many Rolls-Royces. He abandoned a half finished Wrightian mansion he’d commissioned. It was never completed. “It’s just a beautiful ruin,” he says.

In 1998, Monaghan shed Domino’s, sold it for a reported $1 billion.

All in order to dedicate his life and for tune to promoting a brand of strict Catholic morality that lies somewhere between the Spanish Inquisition and the dawning of Vatican II. He believes the three-year church council in the early ’60s—which many saw as a liberation of the church, giving it a more worldly inclusiveness—had a watering-down, morally weakening effect on the church’s authority. Catholics stopped going to confession and started going to therapy. Nuns in elementary schools stopped teaching the catechism and taught pop psychology instead.

What could have caused the nuns of a generation that had been steeped in the catechism, a pre–Vatican II generation, to so quickly change?

“The Devil,” he says, and chuckles and tries to recant, but cannot. “I don’t know,” he says, “but that’s certainly part of it.”

After Vatican II, Monaghan says, “there wasn’t much in the way of dogma or the commandments, confession, let alone birth control. But it’s coming back now; it’s com ing back big. It’s exciting.”

Today, Monaghan’s Ave Maria rubric has come to represent a sort of Domino’s like Catholic brand name, with franchises: There is a charitable foundation to support conservative Catholic causes; a political-action committee to donate to the campaigns of antiabortion, antigay candidates; an in vestment fund; a Catholic radio network; a dating service; a law school; and a liberal arts college to armor the next generation of soldiers of the Lord. But a city named Ave Maria is of an entirely different magnitude.

Still, Monaghan’s role in developing Ave Maria town was largely uncontroversial until, in the summer of 2005, he had a moment of righteous optimism and public-relations brain-lock that could only be called honesty. Speaking before a Catholic-men’s conference in Boston, Monaghan touted the great interest his unbuilt town had sparked. Already, he said, its Web site had received thousands of inquiries from people interested in moving to Ave Maria, all of them Catholic.

We’re going to control all the commercial real estate, so there’s not going to be any pornography sold in this town,” he said. “We’re controlling the cable system. Our pharmacies are not going to be able to sell condoms or dispense contraceptives.”

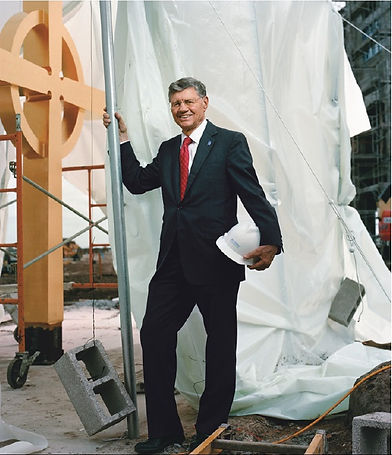

*Former Domino’s CEO and Ave Maria cofounder Tom Monaghan at the town’s construction site.

Immoral or not, contraceptives, pornography, and racy cable TV are all legal in this country. In the ensuing weeks and months, the blowback ranged from alarmed to hyperbolic. Perhaps the most egregious accusation found voice that autumn in a Wall Street Journal opinion piece that asked the question in a subheadline: should ave maria be part of a “catholic jonestown”? And for the next two years, as construction of the Catholic utopia got under way, Monaghan and his development partners backtracked to anyone who would listen.

Nicholas Healy, president of Ave Maria University, who was among the spokesmen dispersed to quiet the outcry, says today, “You know, there’s a difference between what Tom would like and what Tom recognizes is legally possible. And they’re not always the same thing. We’re not going to break any laws.”

Surely not. But a fog of rectitude still hovers over the Ave Maria project, along with a sense that if you block out the evil influences of the culture there, moral purity will flower and the rest of the world will follow suit. It’s a familiar urge, especially for conservatives still seeking Ronald Reagan’s mythical shining city on a hill, which itself was a reference to John Winthrop’s seven teenth-century utopian model.

“One of the fundamental motivations of experimental communities,” says utopian scholar Kenneth Roemer, “is the notion that other places are just too corrupt and what you need to do is go off and establish a model, and if that model is good enough and is successful enough, then people will turn around and say, ‘Hey, that’s what we should do,’ and then your model will double, triple, and multiply.”

***

But what if you build a shining city on a low-lying plain and no one can find you? It takes a good forty-five minutes along flat country roads to get to the site of Ave Maria from Naples. Just as you begin to question your directions, the signs begin to pop up: ave maria two miles. ave maria next left. ave maria: every family. every lifestyle. every dream. Somewhere beyond the trees and endless vegetable fields, set on flat, sandy former ocean bottom, the 5,000 acres of a virgin town await you unseen. Have faith.

Certainly, its founding partners have taken a giant leap of it.

In 2002, Paul Marinelli saw news reports that Tom Monaghan, unable to convince the Ann Arbor zoning board to let him build a new AMU campus on land he already owned, was looking to relocate his college to southwest Florida. Marinelli is president of Barron Collier Companies. For years they’d been looking to develop some of their tens of thousands of acres of rural land in Collier County’s vast and unpopulated east. But they needed a draw to entice residents out to the hinterlands, and Monaghan’s university seemed just the thing. So Marinelli made an offer: Monaghan would get 800 free acres of land for his campus; he would purchase the land around the campus from Barron Collier, where together they would develop a town. And there Monaghan the lay architect and Monaghan the lay priest may well be finding their ultimate expression.

The map of America is dotted with towns built by utopian visionaries (academics call them intentional communities), towns born not because there was a big river or a gold mine nearby but because someone was seeking to escape the corruption of the outside world or to experiment with some notion of urban perfection. Some, like the Shaker villages of Massachusetts or the Mormon cities of Utah, were inspired by God. Others, like Disney’s Celebration, Florida, were the realization of one man’s vision of a perfect, if mythical, America.

Whereas many recent intentional communities have based their designs on walkable American towns from a century ago, Ave Maria, especially its downtown, the design of which Monaghan influenced, is based on a medieval model in which all life, learning, and commerce spill out from a centralized, oversize symbol of devotion to a Christian God.

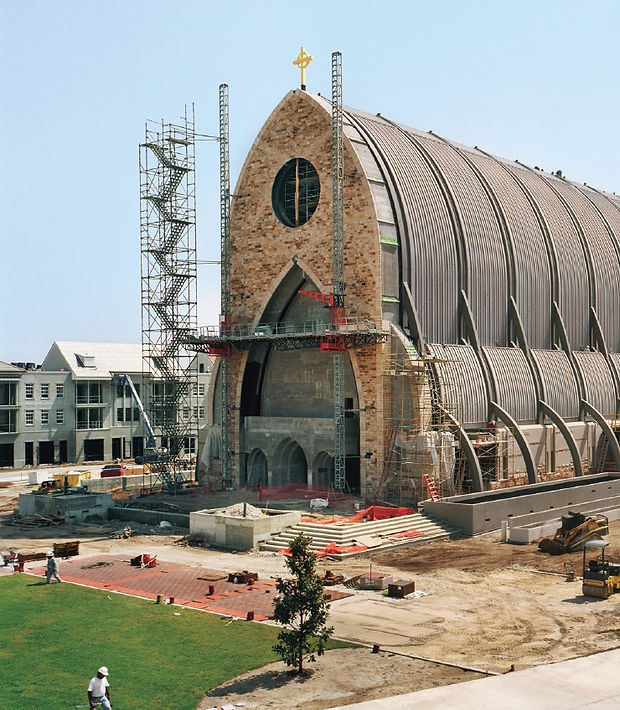

Five years after Monaghan and Marinelli struck their deal, crowning the central piazza of downtown Ave Maria is a colossal beige-and-charcoal-colored steel, glass, and travertine Catholic shrine. Part Gothic, part Romanesque, with steel flying but tresses like warped crutches, it looks like a cross between a bishop’s hat and a medieval battle helmet. Monaghan first sketched the building for designer Harry Warren on a tablecloth. Its dimensions have shrunk as the cost of the project has increased, but it is still enormous, still the confident signature of the relentlessly flat town and campus.

The structure is 104 feet high at the nave—“six feet shorter than St. Pat’s in New York,” says Monaghan with a trace of regret—and adorned by a thirteen-foot tall cross. It will seat 1,100 people and feature a twelve-foot crucifix over the altar. It is cathedral-sized but technically cannot be called a church, because it is not yet officially part of any Roman Catholic diocese. And so it is called an oratory, which refers to a private church or chapel. It will host hourly Masses. It will be the landmark and soul mark of life in Ave Maria.

*An oversize Christmas decoration, provided by Monaghan, stands in wait on the outskirts of Ave Maria town.

Curving around the avenue, horseshoe ing the giant church, are brightly colored Mediterranean-style concrete-and-glass buildings designed for first-floor commerce and upstairs living. Monaghan has already bought a condo on the piazza. He will live there when he is not in Ann Arbor and when his wife is not with him in Florida, where she prefers their home in Naples for now. On bachelor trips to Ave Maria, Monaghan will enjoy a view of the church from his balcony and an easy walk to the university of which he is chancellor, perhaps the only one in America without a college degree.

In contrast to the neo-Mediterranean downtown, the academic and dormitory buildings of Ave Maria are in the long, low Prairie style of Wright, with sand-colored outer walls and greenish copper roofs extending into eaves that might create a scrap of precious shade on blazing southwest-Florida afternoons in August.

For now, the students wait patiently on the moribund temporary campus in Naples, where, as on any campus, I saw attractive young women and gawky boys carrying large books. There were abundant antiabortion bumper stickers on the cars. One proclaimed u can’t b both catholic & pro-choice. Whereas on most campuses, even private ones, you could probably just walk up to students and strike up a conversation, the young people of AMU seem to have had instilled in them a leeriness of the secular world.

They also seem fairly sheltered.

Even though I asked many times to meet with students while I was in Naples, when I finally interview two young men, it is arranged for me by Monaghan’s public-relations office in Cleveland and is over the phone, and there are others in the room, watching them.

More than a quarter of the 400 or so students currently enrolled at AMU come from the growing Catholic home-school movement, including Ryan Tompkins, a 21-year-old junior from Tampa majoring in economics. Tompkins says he appreciates the sense of community and support at AMU. “I would say that there is a really heavy pressure on people who try to live up to morals and stuff,” he says. “I knew that at least here, not only would my faith be strengthened, but when I do go to the outside world, I can help. Instead of me being formed by the culture, I can help form the culture in my own small way."

“I think we’re being formed,” says AMU student Christopher Ortega. “We’re given our armor. We’re given the capabilities to confront the world.”

Christopher Ortega is in the theology program at AMU and, like many of his classmates, is considering the priesthood. Ortega went to public schools in Los Angeles, where it would have been hard to avoid the battleground issues of abortion and gay rights. I ask him how he’d react to a gay student at Ave Maria who wanted to continue practicing his faith.

“I would just continue loving them,” says Ortega. “I would hold that you are created in the image and likeness of God, and God desires to be in a relationship with you. When any person begins to dive into a relationship with God, they begin to discover what actions are good and which are really just driven by their own passions and selfish desires.”

Neither is aware of any openly gay person on campus. Neither believes they are overly sheltered at AMU.

“I don’t think we’re being protected,” says Ortega, “I think we’re being formed. We’re given our armor. We’re given the capabilities to be able to confront the world.

***

After a few days around Ave Maria, I begin to see Monaghan, just a little, as a blue suited militant Moses leading his people away from persecution and into the Floridian promised land, to retrench in the battle against modernity’s onslaught.

“It’s sort of a race,” he tells me in describing his conservative, dogmatic brand of Catholicism and the forces working against it. “You’ve got all the bad stuff, you’ve got MTV and pornography on the Internet, all the other stuff on one side, and then you’ve got all this new wave on the other.”

Maybe this is why the notion of a conservative, Catholic-influenced town to cushion his Catholic university from the polluted, relativist winds of the culture appealed to Monaghan. The town of Ave Maria would be like a rampart in a battle plan for the besieged.

It’s a little strange for an ambivalent creature, even one such as myself, with a love for the Roman Church deep in my Irish blood, to journey into the land of the devoted, daily Mass-going faithful or to imagine living in a town populated by utterly persuaded Ave Maria Catholics. When Monaghan asks me if I am a practicing Catholic or if I just call my self one, all I can say is that here among the Ave Maria folks, given some of my own conscientious objections, I feel like a bad Catholic. Like most of us, I haven’t said a Rosary or gone to a weekday Mass in years. My loss.

In many ways, I am just the kind of Catholic that most troubles him: interested in the direction of cultural change, overly worried about public perceptions, inadequately worried about the souls of others, too busy searching my own soul to simply do and believe what I am told. Frankly, both this feeling of inadequacy and the possible ascendancy of Ave Maria Catholicism trouble me.

Still, as I sit with Monaghan in his small office at AMU, I tell him how much I admire his ability to practice his faith so vigorously, and to stand fast in his beliefs in the face of sometimes angry opposition. I admit to him that there are times, when my Catholicism is questioned, that I falter, clam up, decline to stand up for my faith.

When I tell him I can’t imagine him doing that, he lets out a pained grunt that I can’t quite interpret and then says, “Well, I hope not. It’s not a trait I’d like to have.” Suddenly, he doesn’t seem like such a mild-mannered midwesterner anymore.

He seems taken aback when I suggest he and the brand of Catholicism he leads might be contributing to the negative perceptions of the Catholic Church—but it’s hard to see how he could have missed that.

“That’s sure the opposite of what I’m trying to do,” he says. But it doesn’t bother him at all. “I’m still very confident I’m doing God’s work. I’m going against the trends of the culture, but I think it’s really needed. I hope that we can have an impact on the church and society, and I think it’s particularly important in the United States, be cause it’s the only First World country that’s still Christian to any degree.”

***

On a flawless Florida morning, Monaghan and Marinelli take me on a tour of what is one of the biggest private construction sites in the country. Anywhere you stand or drive in the sprawling, bustling work in progress called Ave Maria, you can see two things: the ridged church dome and, off in the distance, Florida pine forests clumped between farm fields. Anyone who moves here will need a pioneer spirit, at least for the first few years.

After our tour, Monaghan, Marinelli, and two others gather with me in a trailer on the western edge of the site to talk about their hopes and plans for life in Ave Maria and to answer my questions about Monaghan’s original vision for the town. The man himself has repeatedly referred me to Marinelli whenever I bring it up. He’s clearly been reined in.

“The straight record,” says Marinelli, “is this is a community with a Catholic university that is open to all individuals from all denominations. We’re trying to create a community that is based on traditional family values. That’s very important to us. And a community where we’re trying to get back to where people live, work, and recreate together and truly create those neighborhoods like our parents had years ago. I think, over the years, we’ve gotten away from that.”

What did our parents have that we don’t have? I ask.

“Every morning, neighbors watching out for neighbors,” says Marinelli. “Children being able to get on their bicycles and go to the park and feeling safe going to the parks. It was just a feeling. We wrestled with how do we really describe it. It was a lifestyle where people care for each other and have a sense of security, protection, and good family values.”

Marinelli assures me, the residents will be able to get whatever cable channels anyone anywhere could get with Comcast, Ave Maria’s carrier. And gays will not be excluded from Ave Maria.

“If in fact somebody proclaims they are gay at the sales desk,” says Marinelli, “we will not discriminate. We are selling them a home. I can’t make it any clearer than that.

I ask if they hope Ave Maria will be racially diverse.

*The vegetable fields along one of the country roads leading to Ave Maria.

“Latinos,” he says, “you know, blacks,” he says in a lowered tone, “African-Americans—we have people from all walks of life.”

Inside the trailer, Monaghan sits to my right, just around the corner of the conference table. He seems a little impatient, starts tapping the cap of his water bottle on the tabletop, over and over again.

I ask him about the controversial statements in Boston, and for the first time he is willing to talk about it with me.

“I got a little carried away,” he tells me. “I said it’s going to be a town with no pornography, no massage parlors, no topless bars, and stuff like that. I felt I could say that because we could rent to whoever we wanted to. And definitely not meaning we’re going to discriminate, restrict just about everything, and that everybody has to worship the way I do. And we’re not going to control the police.”

Of course, lots of small towns have no massage parlors, no porn shops or topless bars. Their commercial prospects in Ave Maria would be minimal, anyway. AMU president Healy had told me these places would get picketed—by students.

Divining the contraceptive question is more complex. Marinelli says that they would not, could not, force a pharmacy not to sell them but have asked for a voluntary moratorium. I ask, all other things being equal, and given the choice between a pharmacy that agrees to honor the moratorium and one that doesn’t, which they would choose to rent space to. Marinelli says he doesn’t want to be quoted out of context, and after some semantic back and-forth he says that all economic elements being equal, if one prospective pharmacy agrees not to sell contraceptives, it will be given precedent, in deference to the wishes of Monaghan.

So there will not be condoms or birth control or morning-after pills for sale in Ave Maria. But you have to wonder if their absence, or even the theoretical absence of pornography, will really mitigate anyone’s darker urges (if darker they are).

Some Catholic thinkers believe this may signal a retreat from the real world. Richard Rodriguez is a Catholic essayist who has written with Monaghan-like gratitude of his Catholic education and upbringing in books like Days of Obligation and Hunger of Memory. “To circumvent temptation,” says Rodriguez, “and say we’re going to establish a village where there will not be the temptation is to really reduce people to a state of enforced innocence. And I don’t think it’s psychologically healthy. In some way, it’s a very beautiful ambition, but it seems to me not exactly where Catholics have to be."

“You can’t go wrong living somewhere where all the roads are named after saints,” says a future resident. “You are blessed for life,” says his wife.

***

Anyone with the money and inclination could live in Ave Maria town, and there does seem to be a lively interest locally. On a Saturday morning, hundreds of prospective residents, most but certainly not all elderly, spill out from under a tent pitched by the homebuilders, waiting to tour the grounds. Most are white, al though I see a few Asian couples and one black family. There are cookies, donuts, bottled water, leaflets, and maps. Every fifteen minutes or so, a trolley-style bus pulls up, loads up a couple of dozen passengers, and begins the half-hour narrated tour of Ave Maria.

Our driver reads from a script. She shows us where the golf course will be, the town houses, the single-family homes, the water park, the business park, the Venetian canals, the nature preserves. We look at the Frank Lloyd Wright–style buildings of the campus and take pictures of the nearly finished oratory.

Using her script, our driver draws for us a picture of a thriving village of laughing children frolicking in safety; of student intellectuals reading Aristotle and Aquinas in sparkling coffeehouses just off the piazza or sipping milk shakes at the burger joint around the corner; of happy families barbecuing with their happy neighbors on man-made lakes as flocks of indigenous tropical birds flutter through pastel sunsets. She rarely refers to Monaghan—she calls him “moy-naghan”—and only once to his Catholicism.

On the tour, I meet a young couple who have already bought a home, although it is not yet built. They expect to move in this August or September. They are excited about the newness of the houses, the natural setting, the piazza, and the Catholic nature of the town.

“I think that is very interesting,” says the wife. “Being that we both are Roman Catholics—you know, why not?”

Her husband says he likes the idea of Ave Maria because “you feel protected in a way. You can’t go wrong living somewhere where all the roads are named after saints.”

“You are blessed for life,” says the wife. “You might have to worry about the priests,” jokes the husband.

But I would imagine that they would welcome every body,” says the wife.

“This is not going to be only Catholics,” says the husband.

I tell them about Monaghan, about his statements in Boston, and about the clarifications I’ve received over the past two days. The husband is skeptical but not bothered.

“I didn’t hear about that,” he says, “but I don’t mind it. Everyone is always going to find a way to go outside and get what they want.”

But the wife is bothered. She is a liberal Catholic, she says. She has friends of different social statuses, different races. She has gay friends.

“I honestly hope that this is open to everybody,” she says, “and if there is a Catholic connotation because of the university and the private school and all of that, so be it, that will be wonderful, but at the same time it has to be open to everybody.”

“You can’t build the Vatican over again,” says the husband.

***

After my tour and a walk through some far-from-finished model homes, I drive over to Immokalee, the only town any where near Ave Maria. A few minutes out, I get stuck behind a slowgoing forklift carrying cases of bottled water seemingly from nowhere to nowhere. I glance around at the flat terrain. In the eastern distance, over a saw-grass-covered berm, I see a large, unexpected clump of buildings that I quickly realize is downtown Ave Maria. Jutting out above it all is the hulking, heavens-seeking church, like a watchful dark-hued ewe protecting her lambs. From the empty road, it all seems so still and lifeless, so unlikely, so utterly alone, so anxiously awaiting the joyful coming of life, of souls. I sit behind the forklift and wonder how anyone could do something like this, at a time like this, in a place like this, and in the faith that the people and their souls will obediently come, trusting that the world will watch and follow, and in the hope that it will lay the seed of some strange, perfect paradise on earth, and that later we will all find ourselves in heaven. For a moment, I want to go back and look at it again. The boldness of its very existence pulls me in and pushes me away. I feel my own faith pale by comparison. I think about how I honor some of what it honors, but at the same time I am the thing from which it is running.

Finally the forklift makes way. I wave to the Latino driver as I pass. He’s wearing a white cowboy hat. Immokalee is five flat miles farther, but it feels like 10,000. It is the opposite of wealthy, white Naples, the opposite of pristine, inanimate, soon-to-be-very-white Ave Maria. Except that the men and women of Immokalee are largely Catholic. They are Haitian, Guatemalan, Mexican, Cuban. I’m told there are quite nice middle-class neighborhoods in Immokalee, but all I see on Saturday afternoon is its lively, teeming Third World main street.

At a dingy, otherwise empty Aztec restaurant, I eat spicy red mole poblano de pollo. My pregnant waitress pares her nails at a nearby table. For some reason, I expect the people of Immokalee to resent the birth of Ave Maria, but they don’t. One longtime resident tells me that it will increase business at the Indian casino. In fact, the Seminoles have plans to expand already. Ave Maria will create jobs for Immokalee’s workers and improve life for its small-business owners, he says.

“They’re building an ultraconservative university there, right?” he asks. “They’re not going to sell condoms in the town, right? Well, those kids are going to need to get condoms somewhere.”

Neither is essayist Richard Rodriguez losing any sleep over Ave Maria, although he does express a certain unease with what the brand espouses.

“There’s nothing in this town that scares me,” he says, “except that I wouldn’t want to be a part of that Catholicism. My Catholicism belongs to a different tradition; it belongs to Dorothy Day, and Flannery O’Connor, and Thomas Merton, who lived in a monastic retreat but who ended up spending his life outside, conversing with Zen, traveling in Asia. The sense that he had as a Catholic was not that his Catholicism was bound by a village but that it had released him to the world. I want to live as a Catholic in the world.”

With my mole-stained shirt, I walk the tenuous boulevard in Immokalee. In dusty parking lots, buses disgorge sagging field workers. Women carrying children file into the dollar store. Denim-clad Mexican cow

boys jaywalk. Occasionally, a shiny Lexus or a midsize rental car cruises past, doors locked, maps unfolding quickly. I recognize one couple from the Ave Maria tour. I understand their outsiders’ caution; for a stranger, there’s a menacing air in impure, imperfect, worldly Immokalee. Whatever purity lives here has been forged in a harsher world of temptation and want, in an authentic, unplanned, unsheltered town where its very survival is a sign of God, or at least a very beautiful thing. From here, Ave Maria seems so intentionally unworldly, almost world-rejecting. It seems at once beatific and bland, gracious and judgmental, idealistic and ideological. And so far away.